Blog

Foods at school may impact later life health

Could policy around increased fruit and veg consumption and restrictions of sugary drinks at school help kid’s health in the long run?

Could policy around increased fruit and veg consumption and restrictions of sugary drinks at school help kid’s health in the long run?

A group of researchers in the U.S. recently set out to gauge whether what students have available to them at school, between the ages of 5 and 18, would alter the risk of death by cardiometabolic diseases, such as stroke, coronary heart disease and type 2 diabetes, later in life.

The study

By using comparative risk assessment, “an analytic process of evaluating and ranking the different factors that contribute to a particular outcome, such as human disease”,1 the model would estimate the effects of fruit, veg and sugar-sweetened beverages (SSB) on diet and body mass index (BMI) in U.S. children age 5-18 years.2

The team of researchers from Tufts University did this by first gathering data:

- from NHANES 2009-2012 survey for BMI and intakes of fruit, veg and SSB

- on the impact of diet-focused policies from meta-analyses of intervention studies

- on the estimated impact on BMI of dietary changes from trial and cohort studies.

Estimations of effect were also made if such policies had been introduced to today’s adults when they were at school, using a long-term meta-analysis of individual correlations between childhood and adult diet; meta-analyses of diet and cardiometabolic deaths; and the data on cardiometabolic deaths nationally.

What did they find?

Elementary, middle, and high school students were eating 1.6, 1.2, and 1.1 servings of fruit a day; 1.1, 1.3, and 1.5 servings of vegetables (potatoes not included) a day; and 1.0, 1.4, and 1.9 of SSB a day, respectively.

While veg intake didn’t shift too much, providing fruit to students could increase intake by 14%, 19%, and 21% and restricting SSB could decrease intake by 1%, 8%, and 6%, for elementary, middle, and high school students.

Not only that, limiting SSB availability through school policy was also correlated with a reduction in BMI for students at any of the three stages of education. And it was assumed some of the improvements in diet would be kept into adulthood.

What about the number of cardiometabolic deaths?

According to the model’s prediction, reducing SSB had the largest estimated impact on the incidence of cardiometabolic disease at 2,418 deaths averted per year. Providing fruits and vegetables were correlated with 2,121 and 165 deaths averted per year, respectively. In total, that’s 4,703 deaths.

In 2012, the National Center for Health Statistics data showed 702,308 deaths were a result of cardiometabolic disease, so the 4,703 deaths possibly averted mightn’t seem like much.

But what we are fed as kids is a contributing factor to health and worth consideration, as it can influence later life dietary preferences, habits and quality. And cardiometabolic death isn’t the only measure of health – quality of life and risk for other diseases can be impacted, too.

“Rather than addressing diet and obesity later in life, I think we can make a really big impact by targeting these kids when they are young,” said study author Katherine Rosettie. “Students consume over one-third of their daily food intake when they are in school, so this is a great intervention setting, because we can implement policies to directly affect diet.”

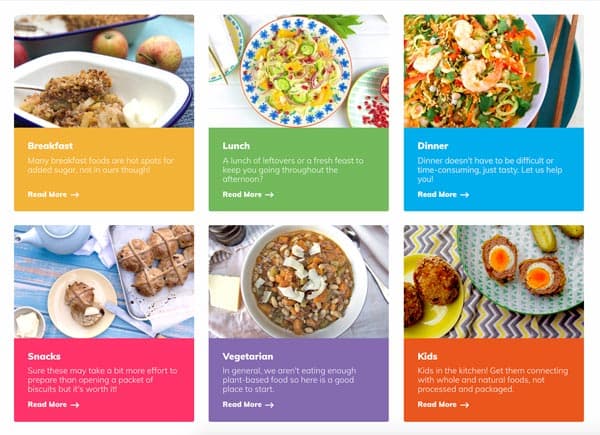

Providers of food and drink to kids and teens can each play a role in ensuring kids get good food, including schools, parents and other caretakers, with the community, government and industry contributing to education and encouragement around healthy and whole food eating practices.

Yendarra School are an excellent example of the influence good food and drink policy at a school can have on health parameters such as weight and tooth decay, as well as learning, behaviour and mood in primary school aged kids.

While school polices aren’t the only influence, it is a factor for addressing the rise of obesity and cardiometabolic disease in our kids. And every bit of positive influence to encourage eating real food over the sugar-laden heavily processed stuff will help.

By Angela Johnson (BHSc Nut. Med.)

References:

- May, RR 2008, ‘Comparative Risk Assessment’, Encyclopedia of Quantitative Risk Analysis and Assessment.

- Rosettie, KL Micha, R Peñalvo, JL Cudhea F & Mozaffarian, D 2017, ‘The Impact of School Food Environment Policies on Child Dietary Intake and BMI and Future Cardiometabolic Outcomes in the United States’, Circulation, vol. 135, issue 01.