Blog

When we eat and cardiometabolic health

Do you reach for something caffeinated or sugary having skipped the conventional breakfast time-slot? Or, do you find following a huge meal at night, although it makes you drowsy (hello, food coma), you don’t sleep all that well?

Do you reach for something caffeinated or sugary having skipped the conventional breakfast time-slot? Or, do you find following a huge meal at night, although it makes you drowsy (hello, food coma), you don’t sleep all that well?

According to a growing body of research, the timing of when a person eats may affect our health.

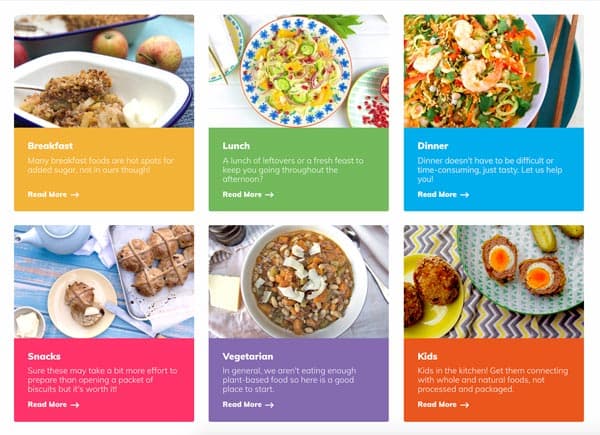

Breakfast for example, has been purported the most important meal of the day for metabolic and cardio health.

You see, compared with the morning, research has identified that insulin sensitivity is reduced in the evening, and those who ate a majority of their food earlier in the day can experience weight loss, reduced liver fat, increased insulin sensitivity and other improvements to metabolic biomarkers.1-3

Skipping breakfast may not be the best idea for your heart, glucose tolerance, or waistline.4

Recently, a team of researchers compiled existing evidence (albeit limited) and concluded that whilst more research is needed, it seems eating a majority of food later in the day might increase risk for cardiometabolic issues, including obesity.5

“Although the evidence suggests that eating more calories later in the evening is associated with obesity, we are still far from understanding whether our energy intake should be distributed equally across the day or whether breakfast should contribute the greatest proportion of energy, followed by lunch and dinner,” says Dr Gerda Pot, one of the article authors.

Evidence is growing to show our body’s internal clock – which regulates the function of all body organs – instigates different biochemical activities depending on the time of day. It is thought eating at regular times may also decrease risk for metabolic syndrome and cardiometabolic disease risk factors.5

“The body and all of the organs have clocks,” says Marie-Pierre St-Onge, an associate professor of nutritional medicine at Columbia University. “There is a timing that provide all the nutrients that organs need, and the timing activity of enzymes and other agents that process food are better earlier in the day than at night.”

Interesting, right?

As we get closer to snooze time, the body is focused on preparing for rest and repair, and activities to help us best utilise our food are down-regulated.

Yet in the morning, the body requires nutrients from food and drink to get through the day, so processes are activated to get as much goodness out of the food and drink we provide to keep us keeping on.

“Meal timing may affect health due to its impact on the body’s internal clock. In animal studies, it appears that when animals receive food while in an inactive phase, such as when they are sleeping, their internal clocks are reset in a way that can alter nutrient metabolism, resulting in greater weight gain, insulin resistance and inflammation,” says St-Onge. “However, more research would need to be done in humans before that can be stated as a fact.”

This can in part explain why shift-workers are at higher risk of cardiometabolic diseases like type 2 diabetes and heart disease, as circadian rhythm, sleeping, eating and lifestyle patterns and habits are all out of whack.3;7-8

Not to forget that affected sleep can drive us to consume more sugary sweet stuff.

Keeping it regular

So, eating regularly, and including breakfast, seems to be a good thing. However, perhaps don’t force yourself a massive early morning feed straight out of bed if you aren’t hungry. But when you do eat, be aware of the quality of what you are eating, as having the right kind of food matters.

Take breakfast for example. Refined cereal and grains are typical breakfast go-to. But having sugar-laden loops or a slice of white bread and jam isn’t setting you up for success, providing a quick spike in energy from nutrient poor food that will leave you needing another quick energy boost shortly after.

Fortunately, what substitutes a breakfast is being redefined! Why not last night’s chicken and salad, if that is what you feel like?

When re-fuelling from the overnight ‘fast’, we want to include nutrient-dense real food that is slow in energy release. Think a combination of complex carbohydrates from vegetables and fruit or a whole food grain like whole oats; healthy fats from nuts, seeds, avocado, coconut or fish; and protein from eggs, fish, nuts, seeds, legumes and dairy.

All in all, routine and eating real whole food seems to be the key takeaway. The body has a natural rhythm and would like to stick to it. Though life doesn’t always accommodate this, we can only try!

By Angela Johnson (BHSc Nut. Med.)

References:

- Kahleova, H, Belinova, L, Malinska, H, Oliyarnyk, O, Trnovska, J, Skop, V, Kazdova, L, Dezortova, M, Hajek, M, Tura, A, Hill, M, & Pelikanova, T 2014, ‘Eating two larger meals a day (breakfast and lunch) is more effective than six smaller meals in a reduced-energy regimen for patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomised crossover study’, Diabetologia, no. 8, p. 1552.

- Lombardo, M, Bellia, A, Padua, E, Annino, G, Guglielmi, V, D’Adamo, M, Iellamo, F, & Sbraccia, P, 2014, ‘Morning meal more efficient for fat loss in a 3-month lifestyle intervention’, The Journal of the American College of Nutrition, 33, no. 3, pp. 198-205.

- Reutrakul, S, & Knutson, KL 2015, ‘Consequences of Circadian Disruption on Cardiometabolic Health’, Sleep Medicine Clinics, vol. 10, no. Science of Circadian Rhythms, pp. 455-468

- Smith, KJ, Gall, SL, McNaughton, SA, Blizzard, L, Dwyer, T, & Venn, AJ 2010, ‘Skipping breakfast: longitudinal associations with cardiometabolic risk factors in the Childhood Determinants of Adult Health Study’, The American Journal Of Clinical Nutrition, vol. 92, no. 6, pp. 1316-1325.

- Pot, GK, Almoosawi, S, & Stephen, AM 2016, ‘Meal irregularity and cardiometabolic consequences: results from observational and intervention studies’, Proceedings of the Nutrition Society, vol. 75, no. 4, pp. 475-486.

- St-Onge, M et al. 2017, ‘Meal planning, timing, may impact heart health’, American Heart Association, viewed 7 February 2017, <http://newsroom.heart.org/news/meal-planning-timing-may-impact-heart-health?preview=557e>

- Jermendy, G, Nádas, J, Hegyi, I, Vasas, I, & Hidvégi, T 2012, ‘Assessment of cardiometabolic risk among shift workers in Hungary’, Health And Quality Of Life Outcomes, vol. 10, p. 18.

- Lajoie, P, Aronson, KJ, Day, A, & Tranmer, J 2015, ‘A cross-sectional study of shift work, sleep quality and cardiometabolic risk in female hospital employees’, BMJ Open, vol. 5, no. 3, p. e007327.